|

Newly opened in 2021, the Provincial Museum Battambang is a real asset to the city. In the immediate vicinity of the old museum (to be seen in the picture on the right), the new museum building was erected (to be seen in the picture on the left). Visitors enter the large hall via a bright anteroom, a kind of vestibule. Even the first glance into the hall gives the impression of an outstanding presentation. Art lovers can breathe a sigh of relief; almost all statues are free and can be viewed from all sides. In the side rooms, too, hardly anything is left to be desired in terms of the arrangement and lighting of the objects. Almost all exhibits are labeled. Best has been done for this museum. The change from the old to the new museum can only be assessed as a successful project. Battambang is justifiably proud of the museum. Unfortunately, there is no advertising for this facility. Not the humblest flyer is within reach. A catalog is out of the question. Attaching a museum shop to the house was probably never considered. There is a lot of catching up to do here, at least according to the European understanding. One of the showpieces of the collection is the extremely beautiful and truly unique Vishnu lintel in the Prei Khmeng style (7th century) from the Prasat Bavel, which is impressively striking in the entrance hall. No comparable lintel from the Prei Khmeng period can be seen in Cambodia's museums, and international (Western) museums have not exhibited anything remotely similar to this point. In short, visitors are fortunate to be able to admire a fine example of early Khmer sculpture. The series of images shows the following deities from left to right:

Prei Khmeng style Vishnu statue (7th-8th c.) Origin: Baset Temple Double-sided stele (Brahmanic Borne) in the Baphuon style (11th c.) Provenance: unknown Front: male deity Back: Ganesha Baphuon-style male deity (11th c.) Origin: unknown The presentation of outstanding exhibits should be limited to the Vishnu lintel and the statues of the gods. Five images provide representative information on the consistently high level of the overall collection in the Battambang Museum. A visit to the new museum in Battambang is highly recommended. Far and wide there is no comparable collection of high-quality Khmer art. Other provincial museums in Cambodia are somewhat smaller and do not yet have the contemporary exhibition standard. Entrance fees are generously waived, donations are expected. Note: Photography is permitted without restrictions Photos and text: Günter Schönlein

0 Comments

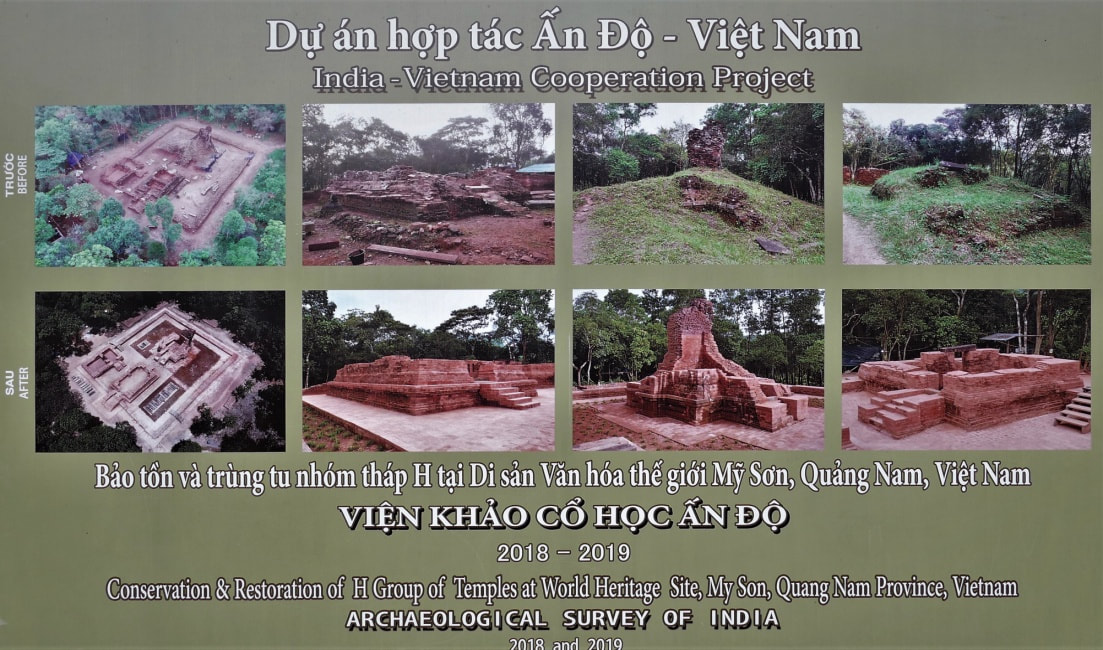

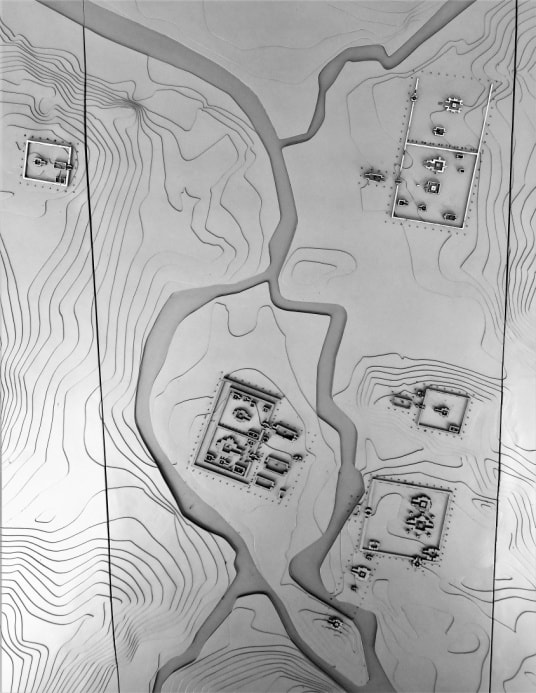

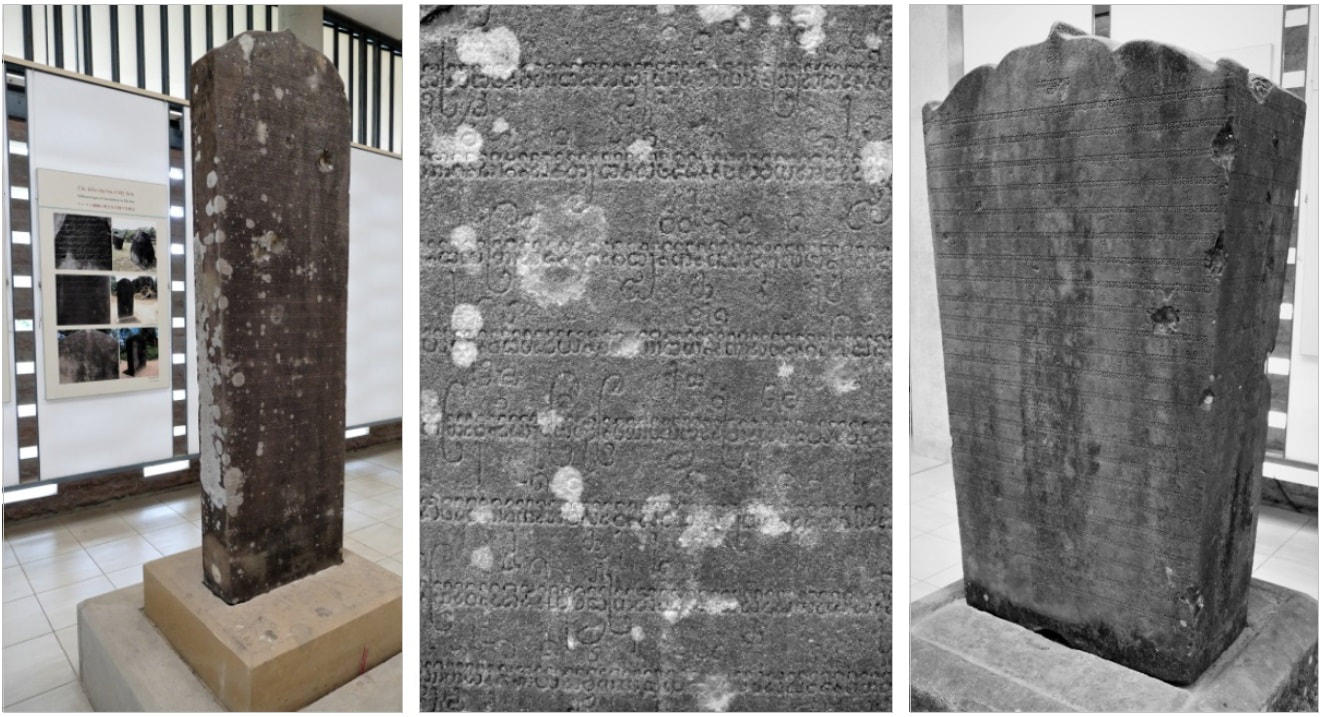

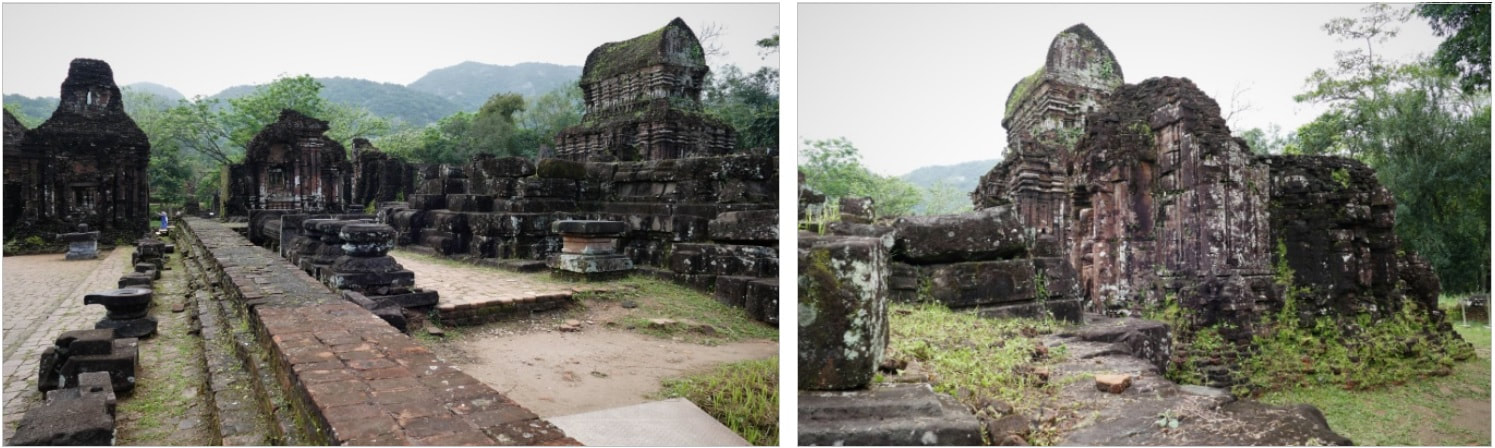

In this final part 5 of the My Son article series, temple group H is introduced and some exhibits from the My Son Museum are described additionally. The ruins of the east-facing H group are just as sparse as the remains of temple group K, which is accessible at the beginning of the circular route (see article: My Son temple town (part 1)). Four buildings stood within the surrounding wall of the regularly arranged temple complex (image 2). Through the Gopura (gateway) H3, people entered the Mandapa (vestibule) H2, south of the Mandapa was the Kosagrha (treasure house) H4, and on the extended central axis stood the Kalan (cella/central temple) H1. Straight walls indicate the dimensions and arrangement of the individual buildings and the size of the entire temple complex (image 3). Only a small amount of wall remains from Kalan H1 (images 3, 4, 4.1, 5). The restorers from Vietnam and India tried to save what could still be saved from the temple complex, which had been completely destroyed in the Vietnam War. The restored ensemble of low walls appears very tidy. All sandstone components were sorted (image 4). Two special components, otherwise not t0o be seen from close by, were set up separately; the high octagonal top must have stood in the semicircular base and decorated the kalan as a crown (image 5.1). Only the north-west view of the Kalan allows us to get an idea of the former appearance of the building structures (image 5). The view over lush meadows into blue distances (image 6) reveals the Cham people's conscious choice of this location for their temple city. My Son wasn't built in any randomly chosen place. Mountains rise above the valley, enclosing the city. My Son means nothing other than “Beautiful Mountain”. One of these hills is said to have considered a holy mountain by the Cham. . . They will certainly have valued the landscape in its entirety as worthy of reverence and respected it as a gift from the gods. Paths to or up any of the mountains are not paved. For visitors of My Son, distant views to the mountains must suffice, although it would be exciting to look at My Son from an elevated position. The My Son Museum in the entrance/exit area is a functional, but not very attractive new building. Right at the beginning of the exhibition, there is a three-dimensional map of the centrally located temples (iimage 7). Here you can see the locations of the temple groups as follows (clockwise starting at 1 o'clock): Temple Group F and Temple Group E Temple Group G Temple Group A Temple Group B and Temple Group C Temple group H The map also indicates the course of the streams. Contour lines illustrate the structure of the landscape. The peripheral temple groups K and L and other temple ruins that are difficult or impossible to access are not included in the papped area. In addition to numerous information boards on the history of My Son, on the structural specifics of the Cham temples and on the rise and fall of the Champa Empire, some objects made of sandstone and terracotta are exhibited, including two steles. In a figurative sense, stelae are the records of the Cham. Scientists value the inscriptions on stelae as authentic sources of reliable information. The Cham steles are often inscribed on four sides, and in some cases even in two or more languages. Donors of the respective temple buildings are named, usually kings, rarely private individuals, the merits of the sponsors are acknowledged, dedications can be read thar inform for whom the temple was erected and to which deity the temple was dedicated, the dates of the inauguration, sometimes of also the construction times, even construction costs are listed, but the builders themselves are never mentioned by name. In rarer instances, written sources are found on columns, door frames or other massive sandstone components. Some Cham temple complexes included a stele house, a permanent building for safekeeping the stele inscription. Leaving information on stelae for the living and for posterity is a tradition that can be traced back to ancient times. Laws were proclaimed on stelae, for example in Mesopotamia. In ancient Greece and the Roman Empire, stelae became established as tombstones, a custom that is still practiced in the Western Hemisphere today. The structural development and aesthetic refinement of the temple facades can also be clearly seen in the gates and entrances, specifically in the pillars that are placed in front of the door frames. Three columns typical of the Cham temples are presented side by side (images 11 & 12). Indian influences are undeniable, but such columns are the very own distinctive creations of Cham artisans. In the temples of the city of My Son, the Shiva cult was predominant, this is why the lingam was worshiped, apart from that, Shiva’s mount was also carved in stone (image 13). The small, barely decorated, naturalistically well-designed sculpture of the humpbacked bull Nandi (Nandin in Vietnam) could have been placed in a separate antechamber (mandapa). The role models for this can again be found in Indian temples. At around the same time, the Chalukya in southern India honoured Lord Shiva, which is why opulent Nandi sculptures are often placed in the mandapes. Nandi and Shiva are often considered equivalent. In the temple, however, the highest reverence is given to the Lingam = Shiva. An unusual example is the lingam with a face shown in image 14. The combination of the aniconic and anthropomorphic forms of representation to form an image of a deity is adopted from Indian traditions, too. Image 15 shows the artistically shaped crown of a temple roof made up of three components or an acroter (external decoration). The square substructure does not fit the acroter, but is of interest because of its inscription. Since ancient times, the production of terracotta objects has no longer been a secret and has been widespread worldwide. Whether smaller statuettes or large statues, sacophages or simply utensils, all shapes are possible. Terracotta pieces have been used as building ceramics until modern times. Since the Renaissance (Luca della Robbia), artists have resorted to the malleable and easily hardened material. The Cham used terracotta reliefs as decorative objects to decorate the temple facades in particular. The Hamsa fragments were recovered in temple group G (image 18). Further examples are exhibited in flat display cases, for example the Naga Kaliya (picture 16) or the Gajasimha (picture 17) or the Kala masks (pictures 19 & 20). Kala masks of the same shape are present in situ on the base of the kalan of temple group G. All those terracotta reliefs of mythological beasts were made in the 12th century. It was impossible in a series of only five articles on the temple town of My Son to explain all the temple buildings in all details and document them with photo; the aim was merely an attempt of a comprehensive overview. The five articles cannot replace a professionally designed illustrated book about the temple buildings of My Son, which is not yet available in German language, for example. The series of articles is only intended as a useful guide to prepare for a detailed visit.

Photos and text: Günter Schönlein Correction of the German Version: Vanessa Jones The temple groups C & B are described and presented with images in part 3 of this series of articles. Part 4 of the My Son article series provides an overview of the exhibits that are presented in two temple buildings of the C group that are used as exhibition halls. Both buildings (formerly assembly halls) each have a single room of a rectangular layout, ideal for exhibition purposes. Mainly objects made of sandstone are on display, some are made of terracotta; it can be assumed that all exhibits are from the temples C & B. Both temple buildings (north and south) must have been badly damaged by the effects of war, which can also be concluded from the condition of the structures. Flat concrete roofs interspersed with windows, which cannot be seen from outside, provide sufficient natural light and protection of the works of art. Proper construction and conservation measures have transformed two ruins into small museums. The placement and hanging of the art objects allows them to be viewed from almost all angles. The inciding daylight makes the objects appear genuine. No museum-style labels were used; in this regard, the visitor’s preparatory knowledge becomes all the more relevant. Two wonderful tympana (images 1.1 & 2.1) attract attention at the entrance of every hall. Shiva can be seen on both reliefs. All exhibits in Hall I are marked with image numbers 1.1 - 1.13, the art objects in Hall II are marked with image numbers 2.1 - 2.16. Exhibition Hall I (Temple South): Shiva can be found in countless variants of depictions in Hindu countries of Asia. The motif of the dancing Shiva can often be seen because it is popular and memorable, although rarely pressed into the high tympanum shape in such a succinct way, as in the Shiva relief in Exhibition Hall I (image 1.1). Two Makaras and two praying people pay homage to the god dancing on a lotus with their lotus offerings. There is no sign of the demon that Shiva is going to destroy while dancing. That is what is actually extraordinary about this motif variant (image 1.2). From a layman's perspective, it is difficult to determine whether a statue or another piece of architecture was inserted into the square recess in the pedestal (image 1.3), and it is equally difficult to identify the headless goddess (image 1.4) by name. Identifying of flying beings (images 1.5 & 1.6) is problematic because both reliefs show some inconsistencies. Figures in this posture are usually female in nature, counting as semi-divine beings, or companions of andharvas (celestial musicians) and are usually recognized or defined as Apsaras or Vidyadharis. Assuming that the left image (image 1.5) is female, the girlish physique and the graceful face make this identification likely, we are then looking at a couple, because the right image (image 1.6) is clearly male, the mustache and the tough physiognomy do not allow any other interpretation. Both carry a weapon, club and/or sword, these props do not fit the semidivine celestial beings. For the reasons stated, no naming is made. Floral decorative elements in the form of foliage (images 1.7 & 1.8) were mostly placed in the upper areas of the temple towers as corner acroters. In image 1.6 (right) you can see another similar decorative component, but this raises the question of whether an extremely stylized Makara can be seen in the leaf acroter. Image 1.7 shows the natural shape of a leaf, while the component in image 1.6 is understood to be a leaf, but differs significantly from the leaf shape. The relief (image 1.8) is reminiscent of an evenly grown tree; here we are probably thinking of the wish-fulfilling tree of life (Kalpavriksha). Gajasimhas, mythological beings that are combinations of elephants and lions, were obviously more than popular among the Cham; due to this preference, they appear in variable forms as relief and statues in front of and on many Cham temples. The Gajasimhas were apparently believed to have special apotropaic abilities. Two attractive specimens of this genus are presented in pictures 1.9 & 1.10. The beautifully worked corner part most likely comes from a pedestal (image 1.11), the relief shows a Kala face typical of Cham art of the My Son era. Next to two steel bomb casings, the torso of a statue of a god is almost lost in inconspicuousness. This unusual presentation will make some visitors uncomfortable, but accusations and critical discussions of the war events and the destruction of the temples in MY SON must be allowed, because it’s fully appropriate. The suffering of the people is all too soon forgotten, and later only the loss of art treasures and material values is lamented. On a long table in the middle of the exhibition hall (image 1.13), in addition to two surprisingly precisely rounded lingam fragments, several parts of external decorations are shown, these are the end pieces of acroteria and decorative tips. A key motif found on the construction elements is the decorative lotus flower, a symbol of purity. The walls still offered enough space for additional objects, but more remains could not be recovered, or the more important pieces were given to other museums. For example, the Cham Museum in Da Nang has magnificent works of art from My Son, which fill one of the halls of the stately house pretty impressively. Exhibition Hall II (Temple North): The inventory and presentation of the objects in Hall II correspond to the exhibition in Hall I. Right in front there is a Shiva tympanum as an eye-catcher (image 2.2). In the wonderfully preserved lower relief area, an ensemble of musicians (image 2.3) is quite impressive: flautist, drummer and dancer in lively movement; today's young audience would attest that the relief is pure action. The right relief part acts as a counterpart to the moving scene on the left: contemplative calm, meditative silence. Does Parvati enjoy homageous worship? Both the left and right images are designed as open-air scenery, with a tree symbolizing nature in each case. There is a small detail worth seeing in the tree in the scene on the left; the musicians probably hung up an incense burner. There are three Nandin sculptures in My Son: a larger one in the My Son Museum and the monumental Nandin sculpture in the open air in Temple Group E (see article: My Son Temple City Part 1 Image 8.10). A third Nandi sculpture, smaller in relation to the others, is shown in picture 2.4. The sculptor knew how a humpbacked bull, like Nandi, should look from the side. The magnificent torso of a statue of a god (shown in four views, images 2.5 - 2.8) is the ideal image or idealized representation of a male deity. With such human sculptures, the Cham sculptors have grown beyond themselves; traditional templates have been overcome and independence has been achieved. The overall photo of the sculpture (image 2.5) shows the massive square base connected to the image and the pyramidal cone, which shows that the deity stood immovably secure on a pedestal. The very elegantly cut and elegantly worn sarong (wrap skirt) does not reveal any peculiarities that indicate a specific deity. The two small fragments with dancers cannot be clearly identified, either. The image 2.9 is possibly a depiction of a Vidyadhari: the posture and veil over the arms indicate such a semi-goddesses, a kind of celestial beings often called Apsaras. – The fragment (image 2.10) does not appear to be a dancer, but rather a warrior. The man's posture shows nothing of dancing elegance; the man strides forward too vehemently and determinedly, towards an goal, the unfortunately remains invisible. Animal reliefs or animal statues are usually guardians. The defense against evil forces (spirits) is entrusted to certain animals. Due to their strong apotropaic charisma, lions (image 2.11) and lion-elephants (image 2.13) seem ideally suited to countering negative forces, as they often appear in the outer areas of the Cham temples. The Hamsa (image 2.12), the sacred goose, is the mount of Brahma (or Brahmi), but its appearance as an individual is rather rare. The Cham priests must almost be said to have a preference for the Hamsa, because Hamsa reliefs have been preserved not only in stone but also in terracotta (see article: Temple City of My Son Part 5, image 18). The torsos of the statues of deities (pictures 2.14 - 2.16) can be easily identified because their mounts are intact, but caution! The equation Humpback Bull Nandi=Shiva is not necessarily correct. The supposedly male upper body is shaped all too feminine; if you want, you can view this torso as Parvati (Shiva's wife). The situation is similar with Brahma (image 2.15). Although Brahmi's female forms are not visible, Brahmi could have sat on the pedestal because she also used the Hamsa as a mount (Vahana). Surprisingly, the torso (image 2.16) is labeled, showing a Dikpalaka, i.e. a guardian of the cardinal directions. Now there are eight, according to some opinions even nine or ten guardians. The Dikpalas (in Sanskrit they are referred to as Lokapalas) include the well-known gods Kubera (North), Yama (South), Varuna (West) and Indra (East), who are lined up around God Brahma in the center. The gods Agni, Nirriti, Vayu and Isana guard the intermediate directions. – The headless Dikpalaka (image 2.16) is depicted with an elephant. Indra is primarily seen riding an elephant, but Kubera is also often seen with an elephant, however, the latter is more commonly a symbol of wealth. The viewer can choose either Indra or Kubera as the sky guardian. Although the sky guardians have illustrious, well-known names, they are rarely spoken of, the reason probably lies in their lesser dominance concerning imagery in stonne. There are only a few reliefs and sculptures of the eight Dikpalas, but they play a significant role in the Hindu written traditions. In order to gain the most comprehensive understanding of the My Son temples and their external and sacred decorations, a visit to the two exhibition halls is essential.

Photos and text: Günter Schönlein Correction of the original German Version: Vanessa Jones Temple groups C & B are barely more than a stone's throw away from temple complex A. The C & B complexes are to be viewed as a unit, it’s difficult to separate the temple buildings, all the temples are built very close to each other. Encircling walls separate the groups of temples, but visually the buildings form a closed unit. Viewed broadly, the temples of C & B face the temple complex A, with only a narrow river separating the temple groups. The valley is well supplied with water, with another small river flowing behind Groups C & B. To the northwest of the temple city, several tributaries join and spread out as Thach Ban Lake. Maps reveal that the area around My Son is lavishly blessed with water. When describing My Son, the temples of C & B must be defined as the center of the temple city. The collection of temples worth seeing amazes the public and poses serious problems for photographers. No amateur photo, no matter how well-made, can capture in a two-dimensional format the overwhelming impression that the double complex actually leaves. It is up to visitors whether they aim for an unattainable overall view or examine each temple as an individual structure. Art enthusiasts will focus on detailed studies with great enthusiasm. The exceptionally shaped door pillars are very striking and are only found here: between the square bases and capitals there are inverted calyxes in opposite directions, connected by a simple central ring (pictures 5.1 & 6). Other unique pieces worth mentioning include some octagonal pillars with wonderfully decorated lotus capitals and bases placed on the ground now. Some of these columns are fluted throughout, others are left smooth over the entire surface (images 6.2 & 6.3). While the calyx columns (name given by the author) are only carved on three sides, the octagonal columns were worked out all around. The octagonal columns are much larger and more massive than the door columns; there must once have been a pompous avenue of columns. A Vietnamese guide loudly announced to his group that if you want to see Roman columns, there are some lying around here. The two longhouses (one newly covered with a flat roof) of Group C are used as exhibition halls. Smaller shrines lack roofs. The state of preservation of the buildings varies. Some temples have been preserved in their full size, such as the Kalan (image 7). Some detailed photos document the magnificent facade decorations. The decorations continue adequately in the roof structure (images 7.1 – 7.5). The asymmetrical design of the facades is remarkable: a counterpart to the continuously decorated, windowless long wall (image 7.1) is the entrance side with the gate placed not right in the center (image 7.5), but one difference is significant: sculptures are missing on the strictly structured rear wall (image 7.1). Instead of it, deep and narrow and very high niches were constructed here. In the niches of the front (and the gable fronts) there are sculptures praying between columns under Makara arches (images 7.5, 7.2 & 7.4). This raises the question: Do they represent human beings (kings) or gods? The gable ends (images 7.2 & 7.4) are largely identical in design: the lower windows are framed by pilasters on which a tympanum rests. Two elephants can be seen on a relief (image 7.3), and this brick relief is promptly touted by the tour guides as Gajalakshmi. The elephants cannot be overlooked, but there is no indication of Gajalakshmi. With good will, the closest thing you can make out is a tree of life. The tympanum above the entrance gate is destroyed (image 7.5). The type of facade design is repeated, in a reduced form, in the roof structure, so to speak, a small Kalan rests on a large Kalan. The selection of photos for the central groups C & B (pictures 1 – 7.5) must in any case be perceived as a limitation, in reality there is much more to see. For this reason, seven additional detailed views are provided: brick reliefs (images 8.1 - 8.3), sandstone reliefs (images 9.1 & 92) and a statue of a deity made of sandstone (images 10.1 & 10.2). The brick relief pictures show four examples of standing people; kings were probably immortalized with these depictions, as already assumed (see above). – The two two sandstone carvings depicting groups (pictures 9.1 & 9.2) are a rarity in My Son: because seven women and one man can be seen, it will be the motif Sapta Matrika, a motif taken from India. – Pictures 10.1 & 10.2 present one of the few god statues that are presented in the open air in My Son. It can be assumed that Shiva is represented here, or otherwise Yama. Note1: Temple group L, listed south of C & B, is not integrated into the official temple circuit; the group is probably only partially accessible.

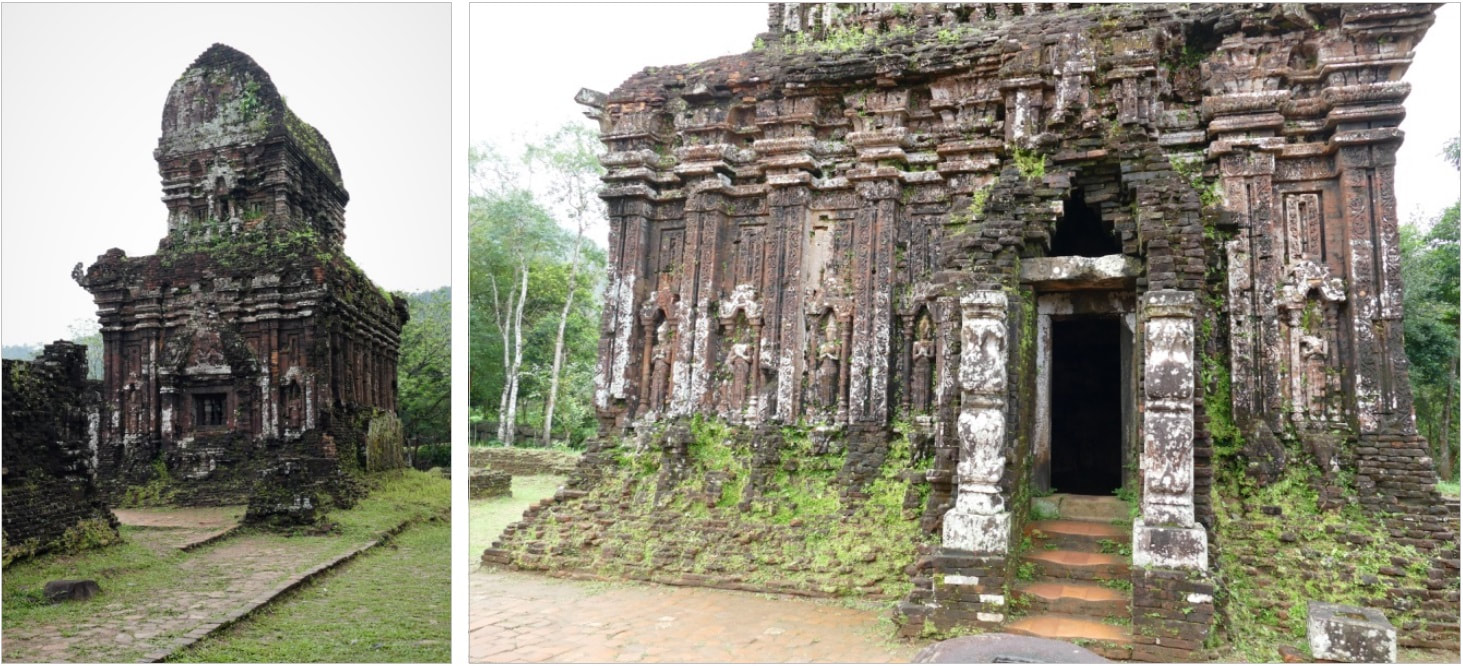

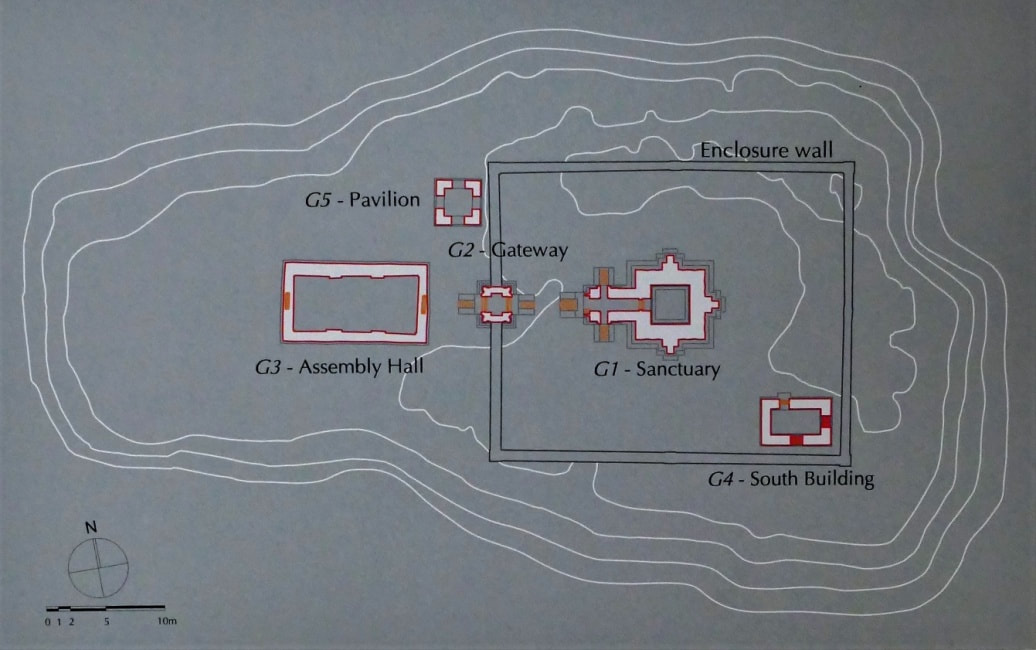

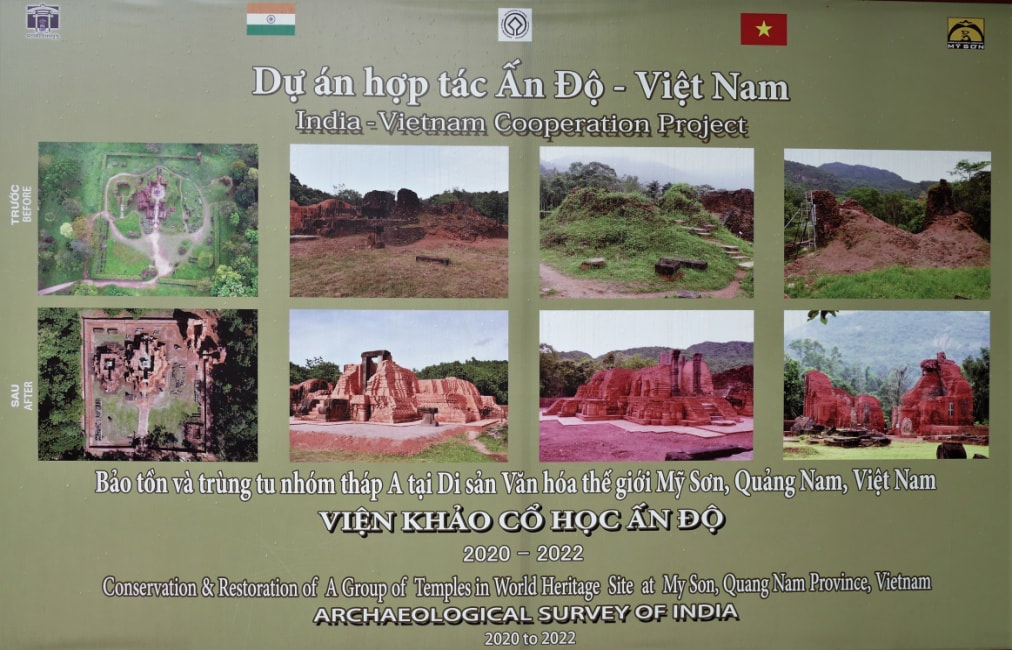

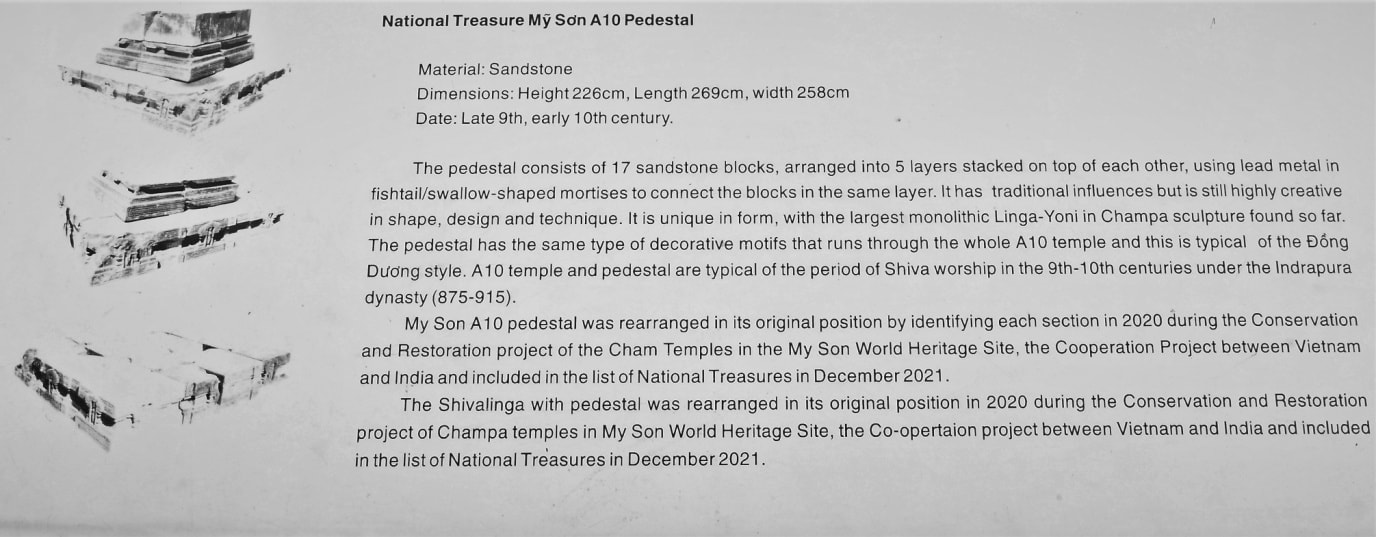

Note 2: Most tourist groups are primarily taken to temple groups B & C, which can get crowded in the morning. If you reach My Son early, try to avoid the crowds by visiting the temples of B & C before ten o'clock. Photos and text: Günter Schönlein Correction of the original German Version: Vanessa Jones Only a few steps separate the buildings of group E from those of temple group G. More guessed than actually seen, because they are surrounded by trees, the complex G seems to consist only of a brick tower (Image 1). Only when approaching directly, you can recognize an elongated rectangle of the base area, on which several buildings stand in a strictly geometrical arrangement (Image 2 & 2.1). In addition to the temple (Kalan), you can see a longer building in front of the gopuram (gate structure) and the stele house in the northwest corner (Image 2). The consistently linear structure of the buildings becomes apparent when viewing it from west to east; only the stele house, which is built outside the central axis, does not fit into the pattern of straight lines, but without foiling the prevailing arrangement of the buildings (Image 2.1). In the southeastern temple area there are low walls of a building the purpose of which remains unclear, perhaps it’s the counterpart to the stele house (Image 2.1 on the right of the temple & Image 2.3 on the right). None of the buildings have survived in their entirety. The small stele house can only be recognized as such because the stele with inscriptions reveals the purpose of the building. Only low wall fragments at different heights indicate the size of the buildings in front of the temple. Solely the temple ruins tower over all other walls (Images 2.1, 2.2 & 2.3). The Kalan (temple) must have had an impressive height. The upper floor and roof structure were probably similar to Kalan E7. The lost eye-catcher is made up for by the structured shape (Image 2.4) and the decoration of the high base (Image 2.5). Only intensive assessment reveals the uniqueness of this foundation. No other of the saved temple buildings in My Son rests on such an exceptionally decorated substructure (Image 2.4). Strange animal statues made of reddish sandstone are inserted at the four base corners. The mythological creatures, which are approximately one meter high, are difficult to identify; they could be upright lions, but the horns and beards contradict this assumption (Images 2.5 - 2.8). It would also be possible to consider the strangely alien-seeming animals as a special variant of Makaras. Also an uncommon form of Yaksha depictions cannot be completely ruled out: nature spirits who are well-disposed towards people, but can also appear with harmful intentions. The most probably accurate interpretation remains to be that these are lions after all, late descendants of the Tra Kieu lions from the 10th century. Whatever animal the strong sculptures indicate, they are among the cultural imports from India, as are the terracotta Kala masks (pictures 2.9 & 2.10). Almost identical depictions of Kala can be found at some Chalukya temples, for example at the Hoysaleshwara Temple in Halebid. The straight wall surfaces of the base are divided into square picture niches. Three-dimensional terracotta reliefs are placed in the niches. The varied, frightening mask-like faces, always of the same type, can be recognized with great certainty as Kalas. Slight differences confirm that each Kala plate is individually manufactured (Images 2.9 – 2.12). Scattered sandstone decorations are integratd in the masonry above the mandapa entrances, these are makaras in the typical stylized form of Cham art (Images 2.13 & 2.14). The ensemble of Yoni pedestals presented in the open air (Image 3) was probably originally located inside the temple. Because of the different materials a connection between the two parts is not obvious. The dark granite of the Yoni doesn't match the base made of light sandstone, and the Yoni and base don't match stylistically, either, which doesn't reduce the value of the solidly crafted individual parts. A statue must have stood on the Yoni; the oval depression does not form a linga cross-section, but corresponds to the substructure of a sculpture (Image 3.1). The middle part of the pedestal with protruding breasts as a decorative element can only be found in Cham art. Similar pedestals are exhibited in the Cham Museum in Da Nang. Walking to temple group A it’s worth taking a look back. Only one building can be made out from the path; you can see the solidly bricked east facade of Kalan G (picture 4). Addition: Unfortunately, a floor plan for the G group is only shown in the My Son Museum. Such a board, placed on site, would make it easier to understand the layout of G temple complex in situ. Temple group A impresses with its size. Group A is in top condition of preservation. The new bricks are shining. The old bricks and the few sandstone parts remaining in the building structure stand out darkly. The restoration measures supported by India were not completed until 2022. A board with eight pictures provides helpful information about the scope of the work (Image 5). Very wide walls surround the square area. The access is on the west side. Despite the large size of the area, several west-facing buildings are grouped tightly together. The middle temple stands on a slightly raised embankment. The flanking buildings on both sides rest on the normal level. In complex A, as in all temple groups presented so far, all sandstone components were sorted and stored separately, these are measures that make it difficult for a non-professional to understand the temple architecture. None of the buildings have been completely preserved. The extent of the destruction caused by the Vietnam war can only be guessed at. In total view, the restored Complex A still appears enormous against the mountainous hinterland. (Image 5.1 & 5.2) Remains of the former decoration have only been preserved in few parts of the wall. It can be assumed that all of the outer walls were decorated with brick reliefs; for example, wide vertical bands with imaginative, varied floral patterns can be seen on the pilasters (Images 5.3 - 5.5). In the lower areas of the wall there are fragments of figural carvings that almost approach sculptural design. A praying man stands between two pillars that support a Kala-Makara lintel, the distinguished gesture does not allow any conclusions to be drawn about what specific deity is depicted. The pictorial representation of a lintel (door lintel) is more important, because such reliefs prove that the Cham indeed created decorated lintels, althoug they rarely used them in their temple architecture, at least not in My Son. The Lintel relief shows an oversized Kala and two Makaras, this depiction is quite clearly inspired by Javanese art. The wall projections to the left and right of the depiction of the praying man would be easier to recognize as elephant sculptures in their original state (Image 5.6). – A human Image literally grows out of the masonry, in the middle of the cornice. Who the striking Image is supposed to represent remains a mystery to the non-specialist; such (supporting) Images can be found in cave temples on the Deccan and in temples in Sri Lanka. Whether this appearance can be aconsidered to represent Yakshas remains uncertain, but among the works of sculptural art this Image can claim to be unique in My Son (Images 5.7 - 5.8). The pedestal A10 can be viewed as a first-class work of art; the dimensions of the altar alone impress the viewer. Average-sized people stand in front of the oversized altar, look upwards and cannot see the yoni or lingam (Image 6.2). The high-quality reliefs on the four sides of the base can clearly be assigned to the Dong Duong style. Attentive visitors will discover very similar reliefs in the Dong Duong Hall in the Cham Museum of Da Nang. By examining the reliefs over a longer period of time, the demands of the fine, detailed sculpture become clear: no Image is the same as another, the faces and clothing of the people are different, and no creeper arch is repeated (Images 6.3 – 6.7). The artistic value of the A10 altar can hardly be disputed; the altar is one of the best pieces that have been preserved in My Son. This work of art deserves weather protection (a roof), but the archaeologists responsible seem to be all too careless in their trust in the longevity of sandstone.

Photos and text: Günter Schönlein Correction of the original German Version: Vanessa Jones

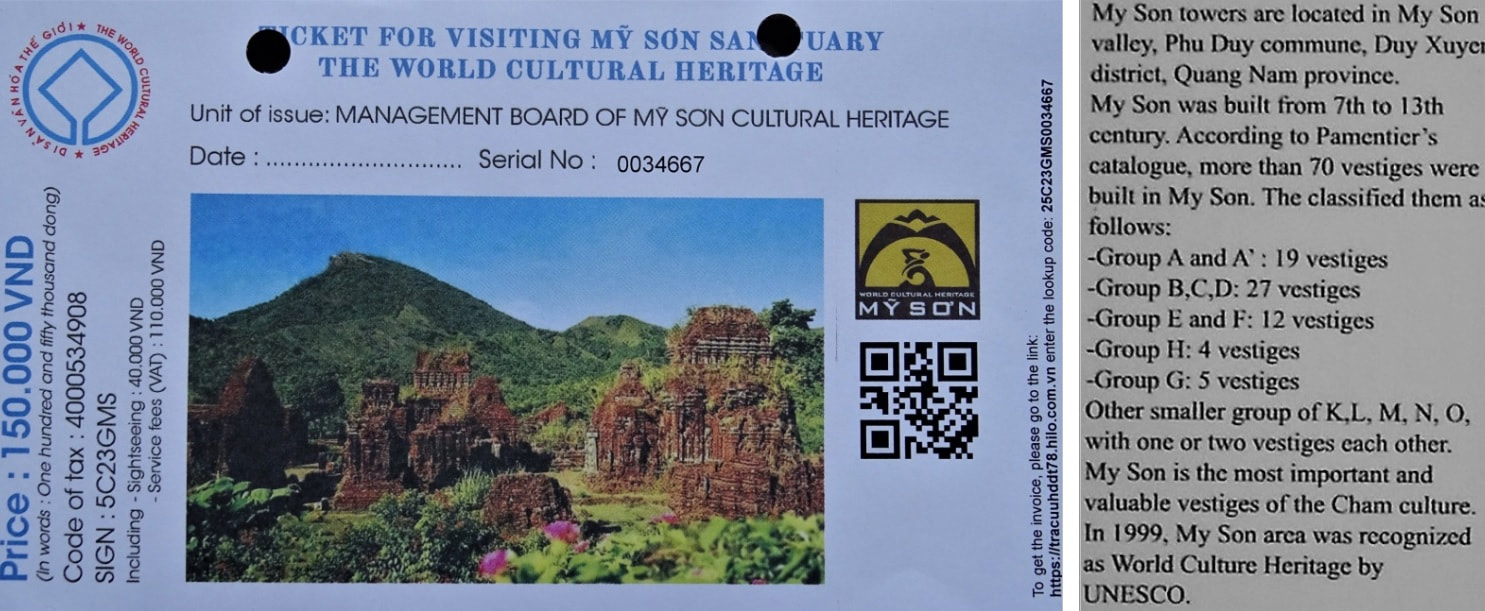

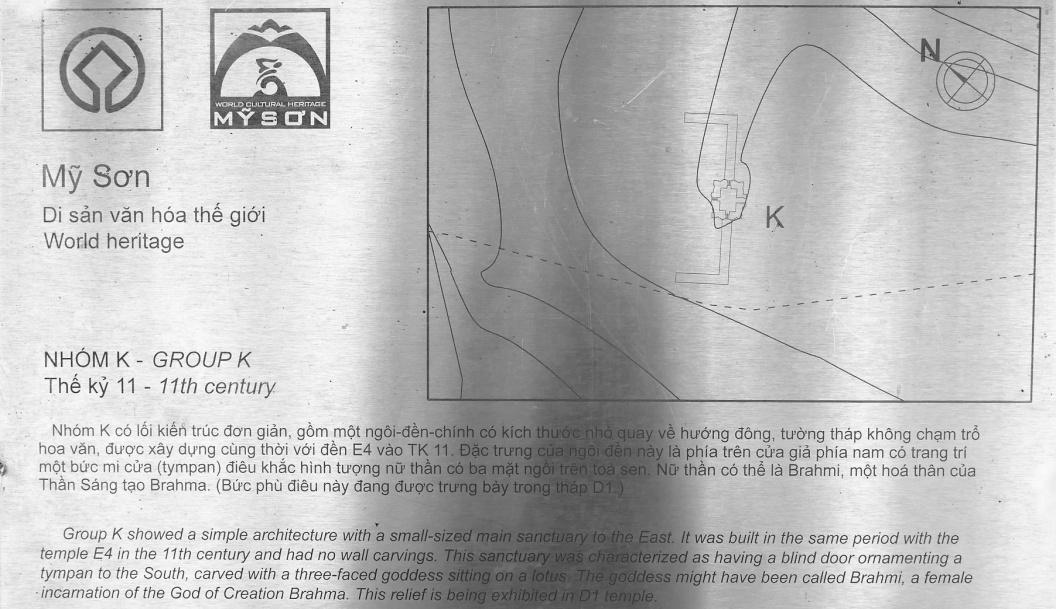

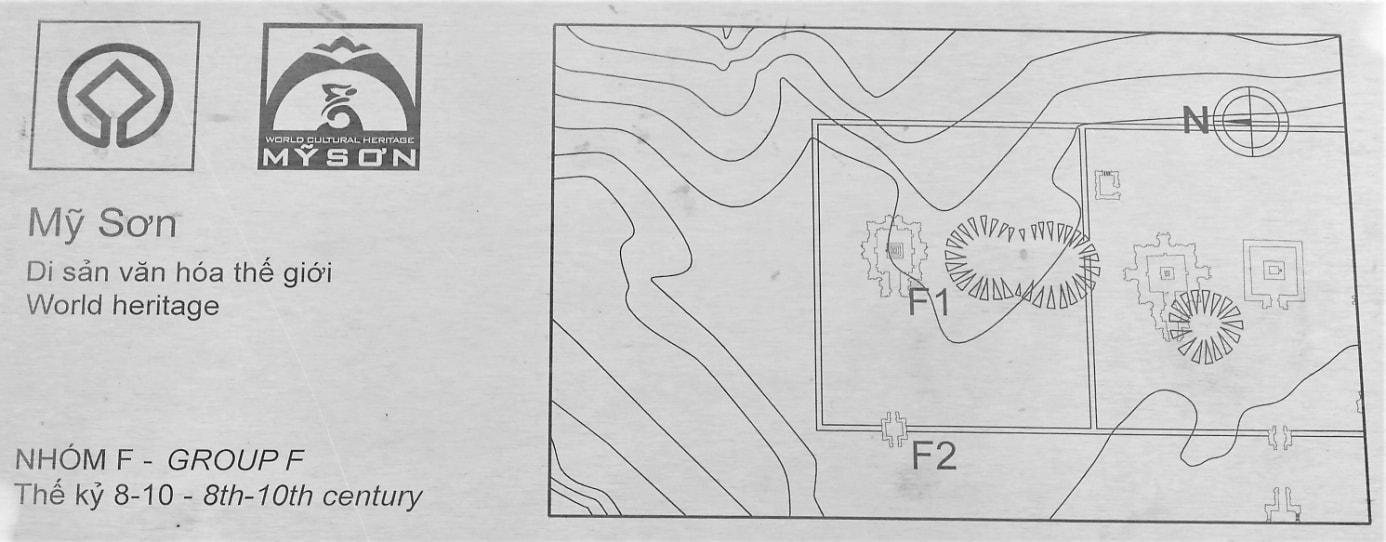

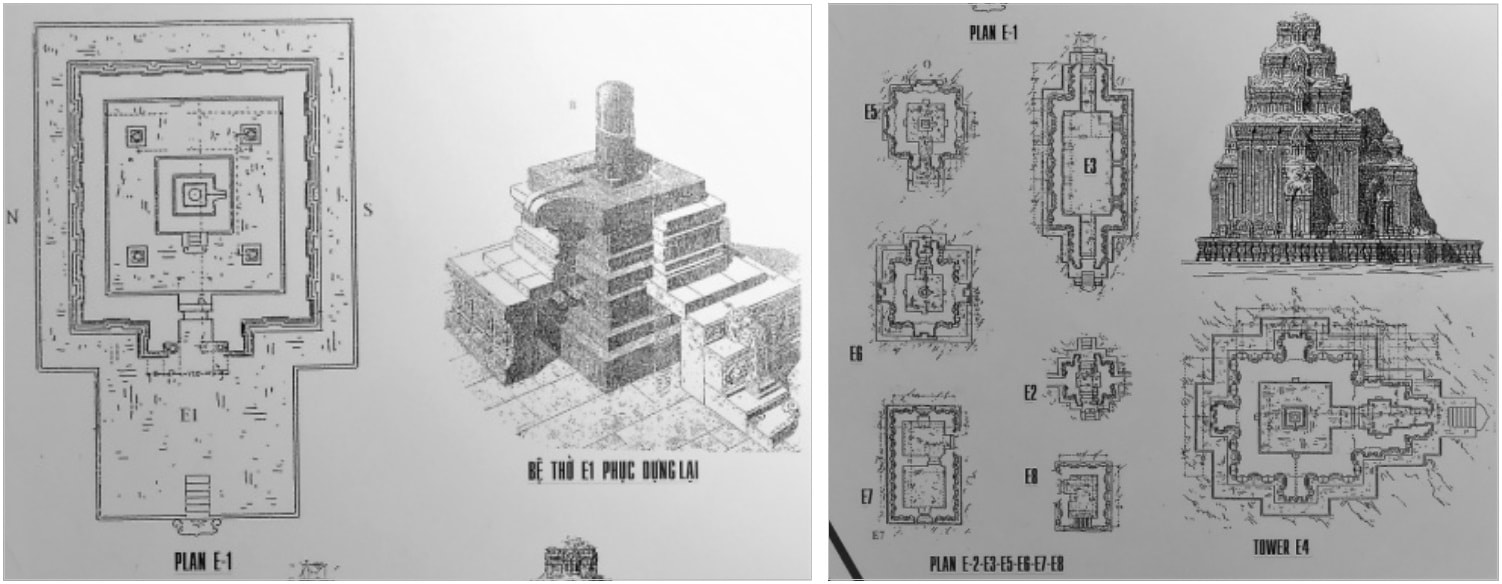

Traveling as a tourist in Vietnam and not visiting My Son borders on ignorance. The temple city is one of the main attractions of pre-arranged Vietnam tours. It's worth arriving early in the morning for a temple visit. The temple complex is accessible from 6 a.m. to 5 p.m. via prescribed routes, which must be adhered to for safety reasons. Anyone who arrives after ten o'clock will hardly be able to see much of the temples due to the crowds. Electric vehicles take visitors from the ticket counter at the entrance to the starting point of the well-prepared circular trail. Orientation boards and signposts are clearly visible. Nobody can get lost. In order not to miss anything and not to miss some temple complexes unnoticed, a site plan should be known or at hand during the visit. However, the exact temple view shown on the admission ticket is not available anywhere on the tour. Nonetheless, the tour is still amazing. You will come to see destroyed and rebuilt Cham temple complexes. Nowhere in Vietnam are there more Cham temples in such a small area. Some of the smaller groups of temples and individual temples are inaccessible or deliberately not signposted because their value for tourists is considered low, and perhaps also because there are no safe routes leading to them. There is a bilingual information board in front of each accessible group of temples, sometimes also along the path: the respective position of the visitor is marked, also drawings of the layouts are displayed (floor plan of the temple). On some boards you can also read short descriptions of the respective temples. The temple groups are largely free of uncontrolled rank growth; the lawns are mowed regularly, but jungle growth is spreading next to the paved paths and up to the edge of the temple complexes. Lush green plants characterize the hilly landscape. Streams flow calmly down the valley. French scientists grouped the temples and numbered them within the groups. If you follow the given circular route clockwise, you first come to temple group K, of which there is only a small amount of buildings left, but it’s still evident with what perfection the Cham were able to build impressive brick buildings. The rare Brahmi sculpture made of sandstone in the brick niche (Kudu) is also noteworthy, because the god Brahma is rarely seen depicted, and Brahmi, the female aspect of Brahma, is even rarer. It is due to good luck that this Brahmi depiction on the lotus throne has survived at its original (?) location and was not destroyed or stolen. However, this Brahmi relief would deserve safekeeping in a museum for presentation. More building structure has been preserved in the clustered temple groups F and E than in group K. In group F, the painful destruction caused by war is particularly evident; bomb craters were not filled in and former temples are hidden under overgrown hills, only piles of rubble remain. One of the most beautiful and largest brick buildings, Temple F 1, can unfortunately only be seen in ruins. The first sight of Temple F1 might shock those arriving there: a high hill of bricks covered by a tin roof, a picture of the greatest possible destruction. Disillusionment and inner movement overcome the visitor, what must have happened here! What mischief was done to Vietnam is known and evidenced by numerous images and films. But at places like Temple Group F the senseless devastation becomes all the more visible in a shocking way. After the visitor has overcome his feelings of sadness, his eyes return to the remains of the temples (Image 7.3). In fact, there are remains of irretrievable brick reliefs on some fragments of the wall. In the upper wall areas (Image 7.4), straight-line structures of pilasters, round columns and false windows have been preserved; in the lower, ground-level wall layers, figural brick reliefs (Image 7.5, top middle and right) can be seen, and some rudimentary decorative bands stand out (Image 7.5, bottom). Sandstone components from temple F1 (Images 7.6 - 7.8) are arranged on the meadow; you can see pillars, thresholds, capitals, columns and a lingam. Perhaps the reconstruction of F1 is considered, or even planned, only the financing is problematic, the crucial question that needs to be clarified is: conservation/maintenance of the building structure or entire restoration = rebuilding the temple. Passing along craters and grass-covered ruins, the equally ruined temple group E is reached after just a few steps on hard-beaten paths (Image 8.1). The rebuilt high Kalan (Images 8.2 - 8.7) of temple group E stands out as an eye-catcher (Images 7.6 & 7.7 can be seen in the background). The term KALAN means temple, also the main sanctuary of a temple complex, and is only used in the context of Cham temples. Kalan is equivalent to Prasat, used for temple construction in Angkor (Cambodia). In Sanskrit, the term Prasada means multi-story building. In Thailand, Khmer temples are defined as prang. Just as the words differ and yet mean the same thing, so too do the temple buildings of different cultures. Cham temples are not to be confused with Khmer temples; their special characteristics can be studied specifically in My Son. A typical illustrative example is the Kalan E7, presented in four side views and two partial views (Images 8.2 – 8.7). Almost all sandstone components from the temple ruins were salvaged and placed in the surroundings of the respective buildings; this statement applies to all temple groups in My Son. For ambitious visitors, the sacred artifacts are of equal interest as the architecture and decorations of the temples. Statues of the deities and lingam-yoni altars could be are objects of preferential attention. Worth seeing is the mighty, self-contained humpback bull Nandi (Nandin in Vietnam). The god Shiva and his mount Nandi are often depicted together on reliefs. Nandi as a sculpture is not only held in particular esteem by the Cham people; sculptures of Shiva's mount are widespread in all Hindu-oriented cultures. Some Hindus believe they worship Nandi as an embodiment of Shiva. Several Nandi sculptures survived the bombardment in My Son, one can be viewed in temple group E (Image 8.10), another one is exhibited in one of the long halls of group C, and a third one is presented in the My Son Museum. The headless statue (Image 8.12) raises the question: are we looking at Shiva or another god? The presence of Nandi and a lingam with yoni in a temple group seems to answer the question in favor of Shiva. The floor plan drawings of the buildings in Temple Group E, which were created at least before the Vietnam War, if not during the French colonial period, illustrate what was lost due to war damage (Images 9.1 & 9.2). In its current state, measurements would only be possible to a limited extent, as only Temple E7 is accessible. Photo 8.10: Vanessa Jones

Photos and text: Günter Schönlein Correction of the original German Version: Vanessa Jones About two dozen monasteries are located in the city of Battambang. Not every monastery is of interest to tourists, but undeterred art lovers should head east of the river to Wat Po Veal. Behind this beautiful temple stands a low simple from outside rather shabby building with barred windows and doors. Consequently, you can assume that valuables are in the rooms. What else could justify this securing of the building? In fact, Khmer relics are stored in the building. Years ago, monks’ hid irretrievable Khmer art treasures in the monastery and with this courageous action saved them from the Khmer rouge’s fancy of destruction. Despite the fact that a sign above the door promises the Wat Po Veal Museum, the collection remains out of reach. Even after repeated requests, no responsible person revealed himself to open the rooms for viewing. Dirty windows prevent you from looking inside. Fortunately, curious visitors smashed several windows at eye level. You have to appreciate this gratefully; the resulting wholes enable views from outside into the hall. The following four photos show the former museum hall, which was once divided with partitions walls. You can still see the course of a clockwise museum tour. With a bit imagination, you can even understand the former arrangement of the art treasures. Dust and cobwebs hardly disturb the unauthorized look at the treasures, but the unbelievable chaos caused willfully is shocking. Ignoring the deplorable conditions, art lovers look at the neglected collection with gratitude and/or sadness. The photos do not require any comments. The remaining remnants and the cultural-historical value of a collection that was once worth seeing seem to have become worthless and meaningless to the owners. The disregard is a scandal. The collection includes what distinguishes Khmer art: lintels, tympana, acroteria, altars and statues. The author could photographically secure some wonderful lintels. These photos only have documentary value. They show art lovers familiar lintel motifs in best Angkor tradition. The differing Kala representations alone will delight art lovers. The Kala-Indra-Lintel, like the Vishnu-Garuda-Lintel and many other objects from the sealed collection belong in a public museum. Probably, all the existing objects recovered in the past belonged to temples of the Battambang region. Speculations regarding the completeness of the former collection are unnecessary. Barbarians have raged, the chaos is unmistakable. It seems that the owners do not feel responsible for the proper storage of the Khmer art objects. The holder of the collection remains unclear to outsiders. The storage hall, you no longer can call it a museum, is invariably located on the grounds of the Po Veal Monastery. The inmates of the monastery disregard the art treasures. With this desolate impression, interested visitors leave things incompletely done and dissatisfied with the otherwise well-kept monastery. The responsibility of the PATA organization for the collection you also have to assess as low. The collection and its preservation are not advertised anywhere. It would be advisable for the city of Battambang or the State Ministry of Culture to take on the protection, care and representation of the collection. Further neglect of these art objects would equate to their loss. Noted with bitterness the collection is currently lost for the public. In the newly built Provincial Museum Battambang, a display board and one object prove the former existence of the Wat Po Veal Museum. King Norodom Sihanouk was certainly the most prominent guest at Wat Po Veal at the inauguration of the museum in 1968, admiring the Bayon period Lokesvara statue (at that time with head). The excellently equipped new museum in Battambang only presents the headless statue, this object proves that at least one work of art from the Wat Po Veal Museum moved to the Provincial Museum. Note: the photos from the Wat Po Veal Museum show the condition of February 25th, 2022

Photos and text: Günter Schönlein Correction: Vanessa Jones |

Author

|

All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2015 Hor Sopheak & Unique Asia Travel and Tours, Siem Reap, Cambodia

Texts and Photos by Ando Sundermann and Hor Sopheak, unless otherwise stated

with special thanks to contributers Günter Schönlein and Jochen Fellmer

Copyright © 2015 Hor Sopheak & Unique Asia Travel and Tours, Siem Reap, Cambodia

Texts and Photos by Ando Sundermann and Hor Sopheak, unless otherwise stated

with special thanks to contributers Günter Schönlein and Jochen Fellmer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed