|

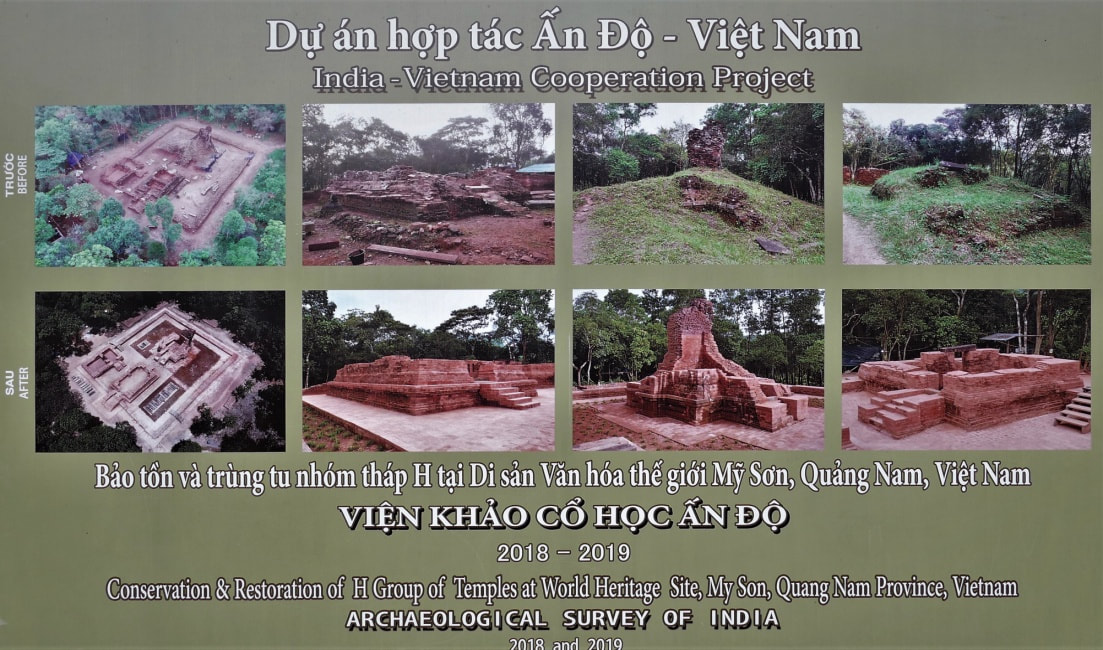

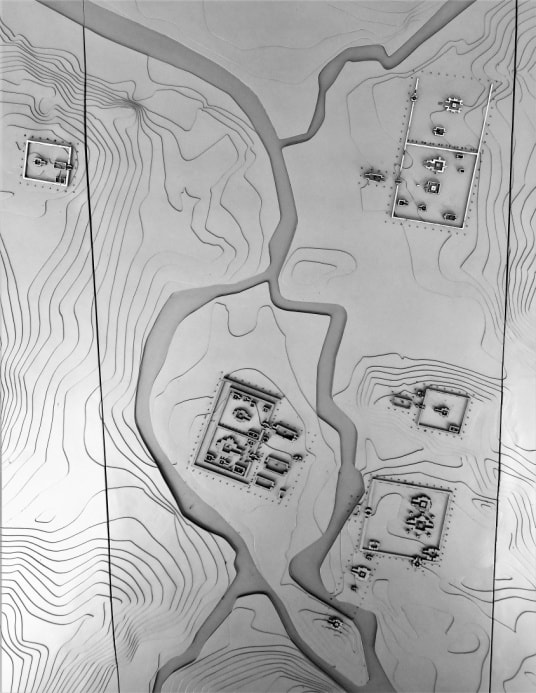

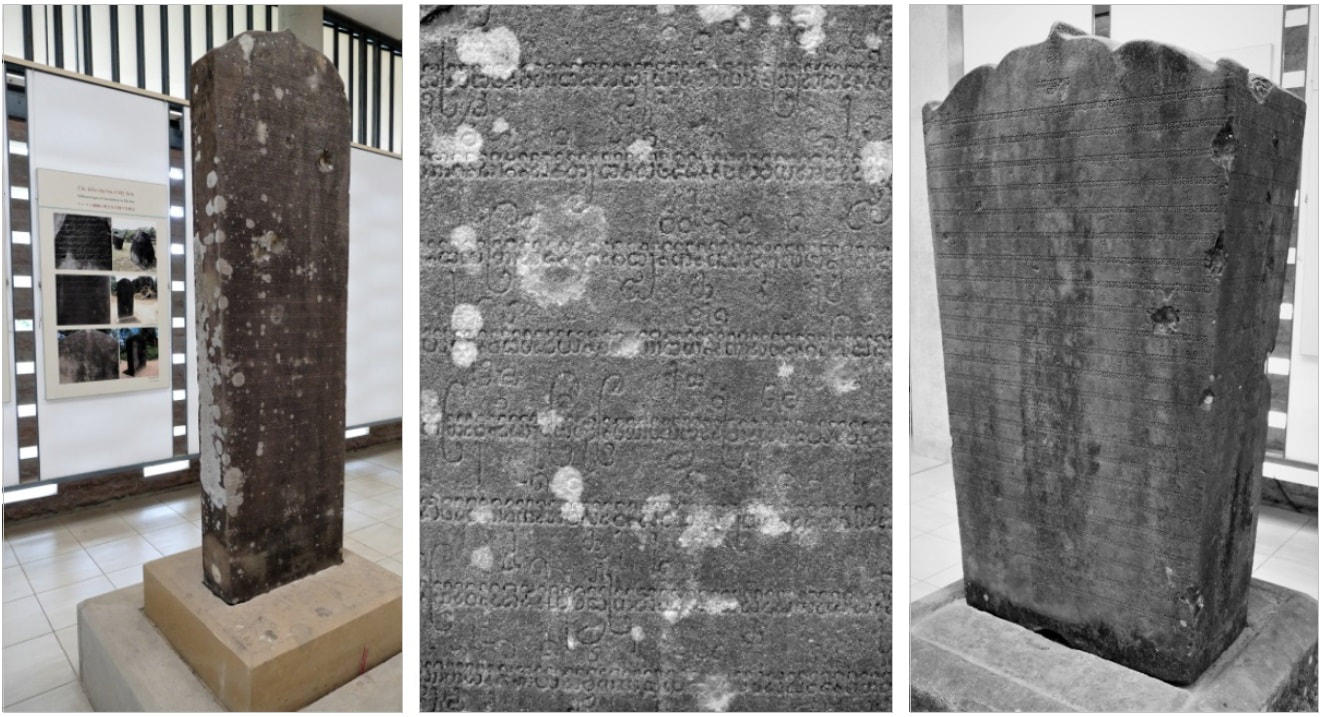

In this final part 5 of the My Son article series, temple group H is introduced and some exhibits from the My Son Museum are described additionally. The ruins of the east-facing H group are just as sparse as the remains of temple group K, which is accessible at the beginning of the circular route (see article: My Son temple town (part 1)). Four buildings stood within the surrounding wall of the regularly arranged temple complex (image 2). Through the Gopura (gateway) H3, people entered the Mandapa (vestibule) H2, south of the Mandapa was the Kosagrha (treasure house) H4, and on the extended central axis stood the Kalan (cella/central temple) H1. Straight walls indicate the dimensions and arrangement of the individual buildings and the size of the entire temple complex (image 3). Only a small amount of wall remains from Kalan H1 (images 3, 4, 4.1, 5). The restorers from Vietnam and India tried to save what could still be saved from the temple complex, which had been completely destroyed in the Vietnam War. The restored ensemble of low walls appears very tidy. All sandstone components were sorted (image 4). Two special components, otherwise not t0o be seen from close by, were set up separately; the high octagonal top must have stood in the semicircular base and decorated the kalan as a crown (image 5.1). Only the north-west view of the Kalan allows us to get an idea of the former appearance of the building structures (image 5). The view over lush meadows into blue distances (image 6) reveals the Cham people's conscious choice of this location for their temple city. My Son wasn't built in any randomly chosen place. Mountains rise above the valley, enclosing the city. My Son means nothing other than “Beautiful Mountain”. One of these hills is said to have considered a holy mountain by the Cham. . . They will certainly have valued the landscape in its entirety as worthy of reverence and respected it as a gift from the gods. Paths to or up any of the mountains are not paved. For visitors of My Son, distant views to the mountains must suffice, although it would be exciting to look at My Son from an elevated position. The My Son Museum in the entrance/exit area is a functional, but not very attractive new building. Right at the beginning of the exhibition, there is a three-dimensional map of the centrally located temples (iimage 7). Here you can see the locations of the temple groups as follows (clockwise starting at 1 o'clock): Temple Group F and Temple Group E Temple Group G Temple Group A Temple Group B and Temple Group C Temple group H The map also indicates the course of the streams. Contour lines illustrate the structure of the landscape. The peripheral temple groups K and L and other temple ruins that are difficult or impossible to access are not included in the papped area. In addition to numerous information boards on the history of My Son, on the structural specifics of the Cham temples and on the rise and fall of the Champa Empire, some objects made of sandstone and terracotta are exhibited, including two steles. In a figurative sense, stelae are the records of the Cham. Scientists value the inscriptions on stelae as authentic sources of reliable information. The Cham steles are often inscribed on four sides, and in some cases even in two or more languages. Donors of the respective temple buildings are named, usually kings, rarely private individuals, the merits of the sponsors are acknowledged, dedications can be read thar inform for whom the temple was erected and to which deity the temple was dedicated, the dates of the inauguration, sometimes of also the construction times, even construction costs are listed, but the builders themselves are never mentioned by name. In rarer instances, written sources are found on columns, door frames or other massive sandstone components. Some Cham temple complexes included a stele house, a permanent building for safekeeping the stele inscription. Leaving information on stelae for the living and for posterity is a tradition that can be traced back to ancient times. Laws were proclaimed on stelae, for example in Mesopotamia. In ancient Greece and the Roman Empire, stelae became established as tombstones, a custom that is still practiced in the Western Hemisphere today. The structural development and aesthetic refinement of the temple facades can also be clearly seen in the gates and entrances, specifically in the pillars that are placed in front of the door frames. Three columns typical of the Cham temples are presented side by side (images 11 & 12). Indian influences are undeniable, but such columns are the very own distinctive creations of Cham artisans. In the temples of the city of My Son, the Shiva cult was predominant, this is why the lingam was worshiped, apart from that, Shiva’s mount was also carved in stone (image 13). The small, barely decorated, naturalistically well-designed sculpture of the humpbacked bull Nandi (Nandin in Vietnam) could have been placed in a separate antechamber (mandapa). The role models for this can again be found in Indian temples. At around the same time, the Chalukya in southern India honoured Lord Shiva, which is why opulent Nandi sculptures are often placed in the mandapes. Nandi and Shiva are often considered equivalent. In the temple, however, the highest reverence is given to the Lingam = Shiva. An unusual example is the lingam with a face shown in image 14. The combination of the aniconic and anthropomorphic forms of representation to form an image of a deity is adopted from Indian traditions, too. Image 15 shows the artistically shaped crown of a temple roof made up of three components or an acroter (external decoration). The square substructure does not fit the acroter, but is of interest because of its inscription. Since ancient times, the production of terracotta objects has no longer been a secret and has been widespread worldwide. Whether smaller statuettes or large statues, sacophages or simply utensils, all shapes are possible. Terracotta pieces have been used as building ceramics until modern times. Since the Renaissance (Luca della Robbia), artists have resorted to the malleable and easily hardened material. The Cham used terracotta reliefs as decorative objects to decorate the temple facades in particular. The Hamsa fragments were recovered in temple group G (image 18). Further examples are exhibited in flat display cases, for example the Naga Kaliya (picture 16) or the Gajasimha (picture 17) or the Kala masks (pictures 19 & 20). Kala masks of the same shape are present in situ on the base of the kalan of temple group G. All those terracotta reliefs of mythological beasts were made in the 12th century. It was impossible in a series of only five articles on the temple town of My Son to explain all the temple buildings in all details and document them with photo; the aim was merely an attempt of a comprehensive overview. The five articles cannot replace a professionally designed illustrated book about the temple buildings of My Son, which is not yet available in German language, for example. The series of articles is only intended as a useful guide to prepare for a detailed visit.

Photos and text: Günter Schönlein Correction of the German Version: Vanessa Jones

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Author

|

All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2015 Hor Sopheak & Unique Asia Travel and Tours, Siem Reap, Cambodia

Texts and Photos by Ando Sundermann and Hor Sopheak, unless otherwise stated

with special thanks to contributers Günter Schönlein and Jochen Fellmer

Copyright © 2015 Hor Sopheak & Unique Asia Travel and Tours, Siem Reap, Cambodia

Texts and Photos by Ando Sundermann and Hor Sopheak, unless otherwise stated

with special thanks to contributers Günter Schönlein and Jochen Fellmer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed